Can Twitter be Chill?

Team “We Love You Bob (WLYB)”

Théophane Mayaud - Basile Spaenlehauer - Abed Alrahman Shabaan

Basic Idea and Project Conception

As the original dataset argues for chilling effects on Wikipedia and shows that such effects may indeed exist and influence people’s behaviour, we saw to inspect the extension of the original hypothesis to another online space.

We chose Twitter as a subject of study instead of Wikipedia having in mind the following differences between the two:

- Wikipedia is mostly an intellectual space, people go to Wikipedia to learn about a certain subject, while Twitter is more of a Wild West of ideas and silly everyday thoughts, and not necessarily dedicated to a specific purpose

- Wikipedia is more of a passive space, there isn’t really a lot of interaction between users and each individual’s behaviour on the website is pretty much independent from the others, while Twitter is mostly a slurry of conversations and people talking to (actually, more like yelling at) each other. So when we look into sensitive subjects (as we are to do in this small study), we can expect a lot of heated debate, and hence a lot of activity incited by recent events.

Research Question

we set ourselves two questions that we seek to answer in this work

1. Do the chilling effects found in the original paper extend to Twitter?

2. Does Twitter show an inverse effect because of its discussion-oriented nature?

Used Data

To have a similar scope to the original paper, we chose to use all Tweets from the same studied period of the paper that contains one of the article titles studied in the paper (more accurately, all Tweets that show up in a Twitter search for those words)

To do so, we used the Python module Twint to scrape the Tweets described above, this choice introduces the following issues to our data:

- The module doesn’t get Tweets from deleted, banned, or shadow-banned accounts, so the observed data will be missing some Tweets.

- How clean will the scraped data be? How many irrelevant Tweets will be introduced into the dataset?

Warming Up (our CPUs)

We went on and recovered the data as planned (after a test run on Twitter Superstar Donald Trump’s account), and retrieved about 65 GB of Twitter Data (Tweets, mentions, likes, etc. as well as metadata) containing the following keywords:

abu sayyaf, agro, al-qaeda in the arabian peninsula, al-qaeda in the islamic maghreb, al-qaeda, al-shabaab, ammonium nitrate, biological weapon, car bomb, chemical weapon, conventional weapon, dirty bomb, eco-terrorism, environmental terrorism, euskadi ta askatasuna, extremism, farc, fundamentalism, hamas, hezbollah, improvised explosive device, iraq, irish republican army, islamist, jihad, nationalism, nigeria, nuclear enrichment, nuclear, palestine liberation front, plo, political radicalism, somalia, suicide attack, suicide bomber, taliban, tamil tigers, tehrik-i-taliban pakistan, terrorism, terror, weapons-grade, yemen

The data recovery went on for several days, probably used enough energy for us to feel bad, and was the biggest bottleneck in our operation.

As a matter of fact, as of the time this datastory is being written, the two biggest Dataframes haven’t really finished downloading (pakistan and attack).

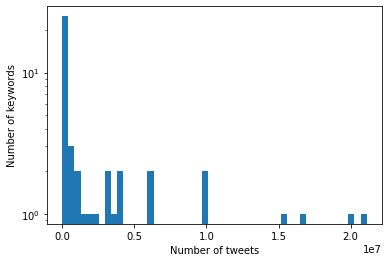

Nonetheless, we were able to retrieve the other 45 dataframes and had 134 million Tweets to work with. The tweets per dataframe had the following distribution

Cleaning Up (our DFs)

Having a quick look at the Dataframes left us with some (expected, but nonetheless hurtful) findings, the data is less than desirably clean, we have Tweets in more than 20 languages (although our work is restricted to English content). This can be handled rather easily as the returned metadata contains the Tweet’s language so we can use that to filter our data down, doing that reduced the size of our dataframes by 25% on average.

The more fun to see but less fun to solve problem is the inclusion of irrelevant Tweets in the dataset. Some of them were wholesome like

Happy New Year everybody !! may 2012 be full of success , love and peace to everybody in the US, Iraq, Middle East and everywhere !!. in the Dataframe Iraq, although some of them were, let’s say less savoury:

“I’m not a dirty whore, I bathe and I don’t get paid. I’m a nice lady who gives bomb ass blowjobs “ well folks, there you have it ; ). in the Dataframe dirty bomb.

We tried removing those through detecting “positive” words specific to each Dataframe, but that lead to the elimination of many relevant Tweets as well (eliminating tweets contatining the word bath in dirty bomb eliminates all Tweets mentioning a bloodbath for example), so the procedure seemed to do more harm than good and we made the choice of leaving those funny Tweets in the dataset as they represented a minority that shouldn’t really affect the conclusion.

Rolling up (our Sleeves)

Accounting for the Interactive Nature of Twitter

It’s not only the writing of Tweets that can be registered by the government surveillance (and hence be prone to chilling effects), but other forms of online interaction as well (likes for example), so in our model we chose to model the total number of action instead of just the total number of Tweets, “action” meaning Tweeting, liking or replying.

We got a total of 183.87 actions over the period.

Modelling the Chaos of Twitter

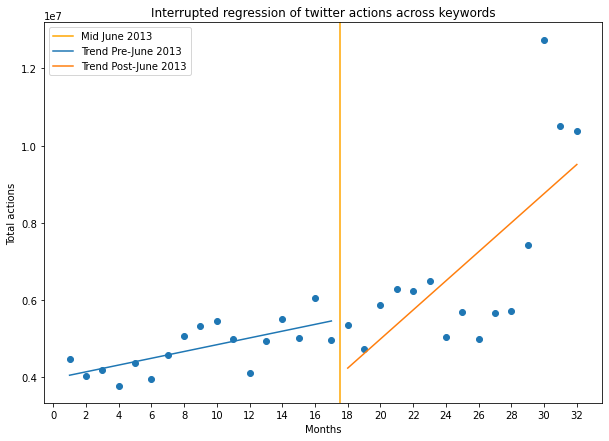

the model we chose to do is a segmented linear regression of monthly aggregated data like in the original paper. This model helps us probe changes in trend in our data before and after the hypothesised chiller event (in this case Edward Snowden’s revelation about U.S government surveillance).

The gives us the following plot:

As we see, the trend in our data does change, but changes rather starkly to increase, and mostly due to extremely high values in the late summer of 2014, those values we deem to be due to the big increase in activity of ISIS during that period, so the terms included in our search became “hot topics” and were often mentioned and discussed over and over again on Twitter. But the other datapoints don’t really seem to show any change in trend caused by the Snowden’s leaks.

Whipping up (our Conclusions)

Seeing the results we obtain, we conclude the following:

-

Twitter doesn’t seem to show chilling effects as Wikipedia did.

-

If anything we see the inverse as more conversations and debates are sparked around such controvercies as government surveillance.

-

Twitter data is a real hassle to work with, but it has some gems that can brighten up one’s day

Looking Back (not up)

In hindsight, we see that our methodology lacked some rigour in data cleaning (removing irrelevant Tweets), and more time should have been spent on that task.

We also didn’t expect the scraping to take such a long time, so we ended up having little time to actually work with the data, so we should have started a bit earlier.